Bitcoin Mining Around the World: Kazakhstan

Kazakh bitcoin miners stand at a crossroads as a new bitcoin mining law is being implemented.

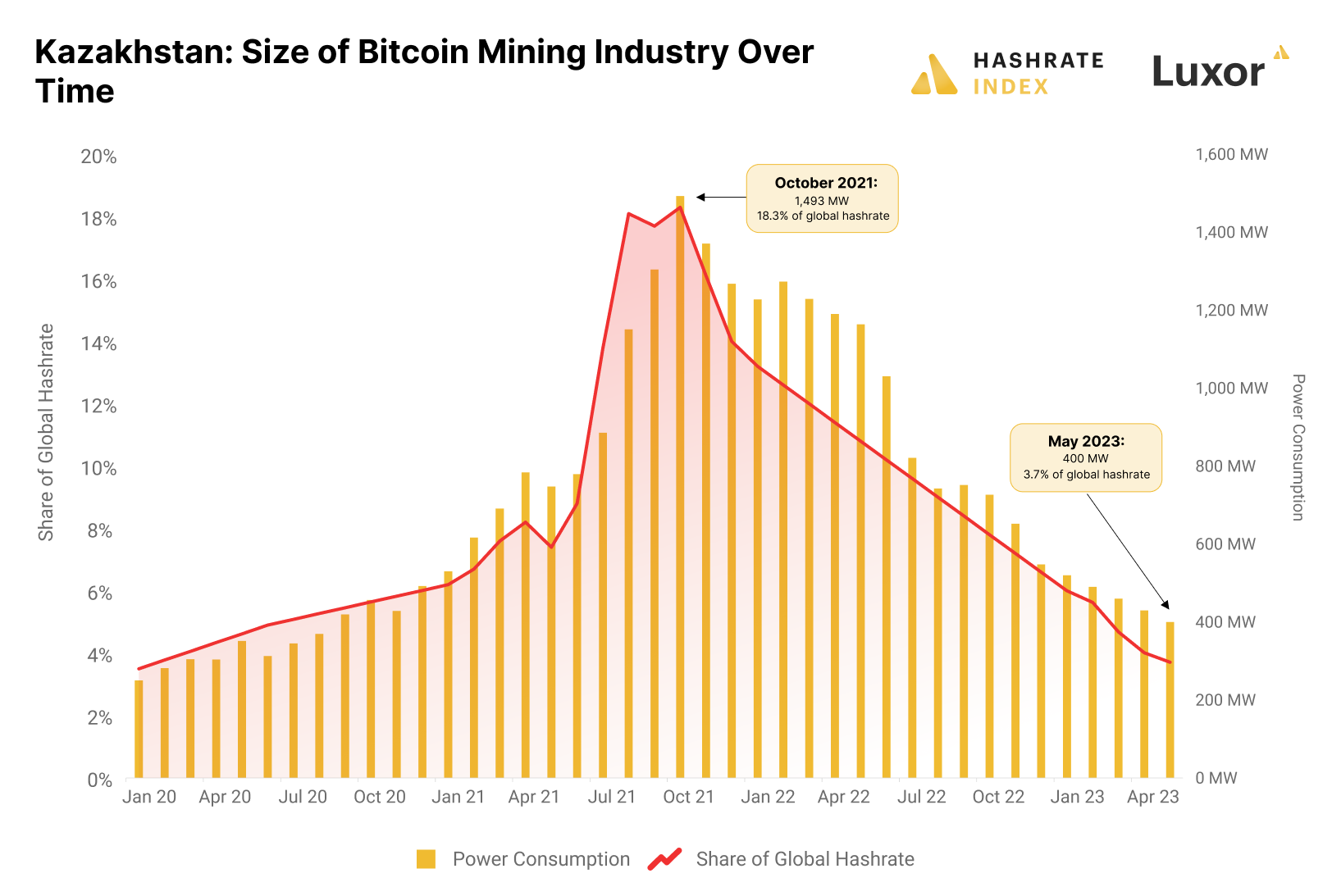

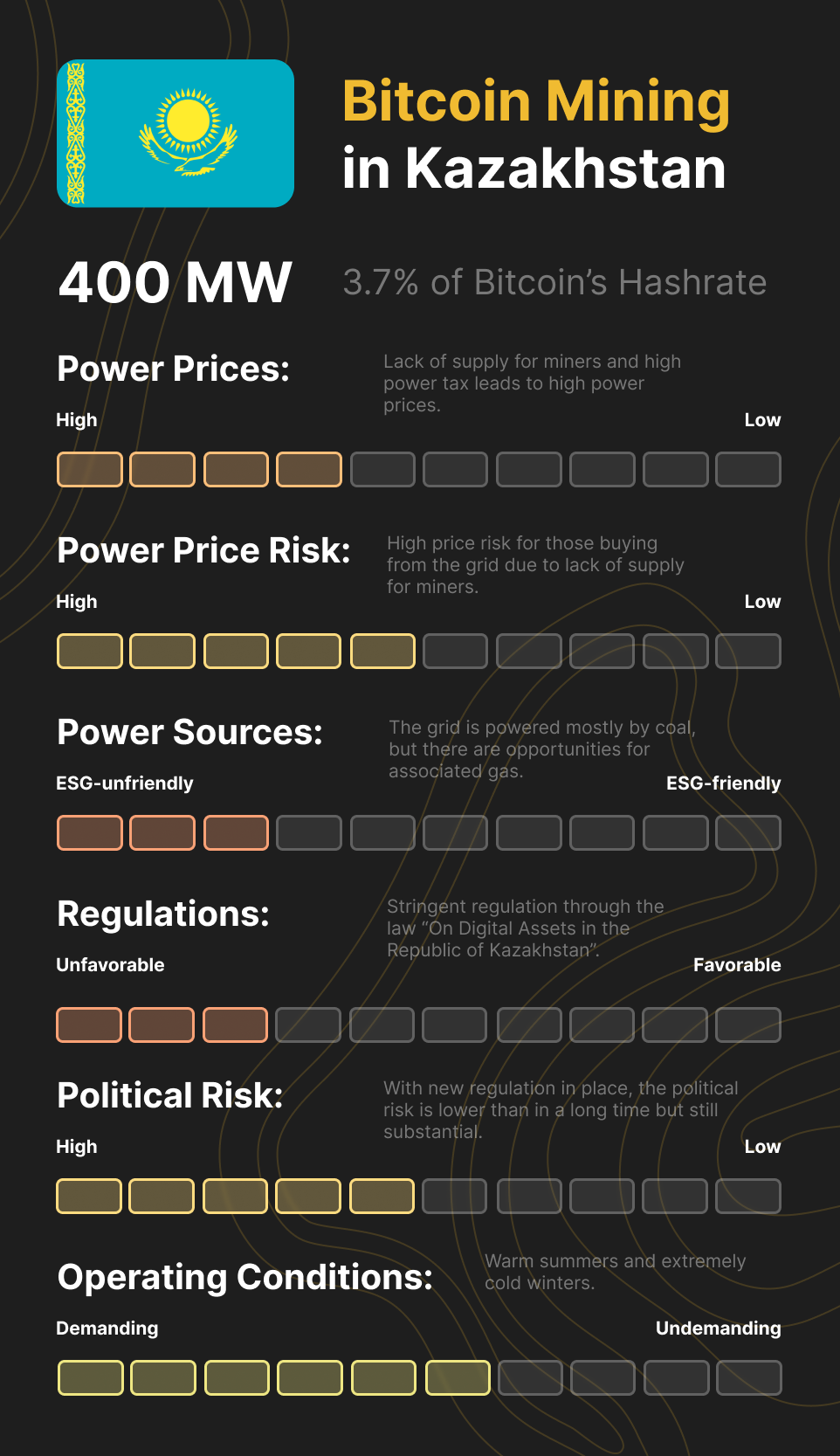

The Central Asian energy superpower Kazakhstan rapidly climbed to second place globally in bitcoin mining in 2021. However, the country’s seemingly invincible bitcoin mining industry soon started suffering from growing pains and suddenly found itself in a horrifying situation of electricity rationing. As a result, the country’s share of the global hashrate plummeted from a peak of 18% in October 2021 to only 4% in May 2023.

Kazakh bitcoin miners now stand at a crossroads as a new bitcoin mining law is being implemented. This regulation is exceptionally stringent but still welcomed by most Kazakh miners, desperate for regulatory stability after being trapped in a Kafkaesque bureaucratic mess for over a year.

I recently spent two weeks in Kazakhstan and met with industry insiders. In this article, I explain what characterizes bitcoin mining in Kazakhstan and analyze how the new regulation could affect the industry. I also discuss what the rest of the world could learn from seeing the political risk play out in the country.

This article is the latest in our Bitcoin Mining Around the World series. Our previous articles cover Sweden, Norway, Iceland, Paraguay, and Kyrgyzstan.

The rise and fall of the Kazakh bitcoin mining industry

Most observers were surprised when Kazakhstan came out of nowhere to become the second-largest bitcoin producer globally in 2021. During this year, the country’s bitcoin mining capacity exploded from 500 MW in January to a peak of 1,500 MW in October, with its share of the global hashrate surging from 6% to 18%. Kazakhstan had suddenly become a bitcoin mining superpower.

However, the Kazakh bitcoin mining party didn’t last long. The industry's size has plummeted since the peak in October 2021, now only sitting at 400 MW, corresponding to 4% of Bitcoin’s hashrate. Kazakhstan’s once great bitcoin mining industry has been reduced to a shadow of its former self.

Let’s do a quick history lesson on bitcoin mining in Kazakhstan to understand what led to the rapid growth and fall of the industry.

Four factors contributed to the outstanding growth in 2020 and 2021. The most critical factor was the abundant access to cheap electricity. The Kazakh government caps electricity prices at between $0.02 and $0.03 per kWh. These price caps gave Kazakh miners access to globally competitive electricity prices.

In addition, the low electricity price caps incentivized Kazakh power plants to mine bitcoin with their power instead of selling it to the grid. If you, as a power plant owner, could choose between making $0.25 per kWh by mining bitcoin or earning a lousy $0.02 per kWh by selling electricity to the grid, the choice is simple, right? Facing this choice, lots of Kazakh power plants installed bitcoin mines directly at their facilities.

The second growth driver was the vast capital inflow from Western miners looking for quick and cheap machine deployments during the previous bull market. Kazakhstan was widely viewed as an affordable and relatively safe place to mine bitcoin, so Kazakh hosting providers had no problems filling their shelves with machines owned by American and European clients.

The third growth driver was China’s bitcoin mining ban in May 2021. Shortly after China’s ban, mining equipment started flowing into neighboring Kazakhstan, incentivizing the buildout of even more mining facilities to house the influx of machines. In addition, unable to sell to the Chinese market anymore, the big rig manufacturers, particularly Canaan, started targeting the Kazakh market more aggressively.

The fourth growth driver was Kazakhstan’s loose regulation and tax breaks provided to IT companies. Kazakhstan is eager to diversify its commodity-based economy and offers several advantages for IT companies. As pseudo-IT businesses, bitcoin miners quickly took advantage of these tax breaks.

Cheap electricity, huge hosting demand during the bull market, vast access to cheap Chinese machines, and loose regulation and tax breaks provided the perfect breeding ground for a burgeoning Kazakh mining industry. Unfortunately, the rapid growth soon started spiraling out of control.

Kazakhstan's total bitcoin mining load reached 1.5 GW in October 2021, up from only 200 MW one and a half years earlier. This is a massive growth, even for a vast country like Kazakhstan. The only way for an electricity system to safely incorporate such a gigantic bitcoin mining load without correspondingly increasing the electricity supply is to ensure the miners turn off their machines during periods of peak demand. This concept is called demand response and has allowed more advanced electricity systems like Texas' to safely integrate hundreds of megawatts of miners and even take advantage of the miners' demand flexibility to help balance the electric grid.

Unfortunately, Kazakhstan's Soviet-era electricity system doesn’t have an advanced demand response system and had difficulties accommodating the sudden mining demand growth. The first rolling blackouts happened in the summer of 2021 in the electricity-deprived south part of the country. The Kazakh grid operator KEGOC soon warned that they might have to cut miners’ electricity consumption.

From September 2021, KEGOC started cutting the provision of electricity to bitcoin miners in the southern part of the country. Things would only worsen, and an increasing number of miners would soon find themselves in the worst nightmare of a bitcoin miner: electricity rationing. Miners could now only use imported electricity from Russia at inflated prices, leading to the bankruptcy of many facilities. Many of those remaining run at limited capacity, only during weekends or nights.

Kazakh miners have struggled heavily for over a year now under electricity rationing and unclear regulation. However, those still operating are more optimistic than in a long time, as a new law was recently introduced, providing regulatory clarity for the industry. Later in the article, I will explain this regulation in detail and discuss how it could impact the mining industry.

Kazakhstan is powered by stranded coal

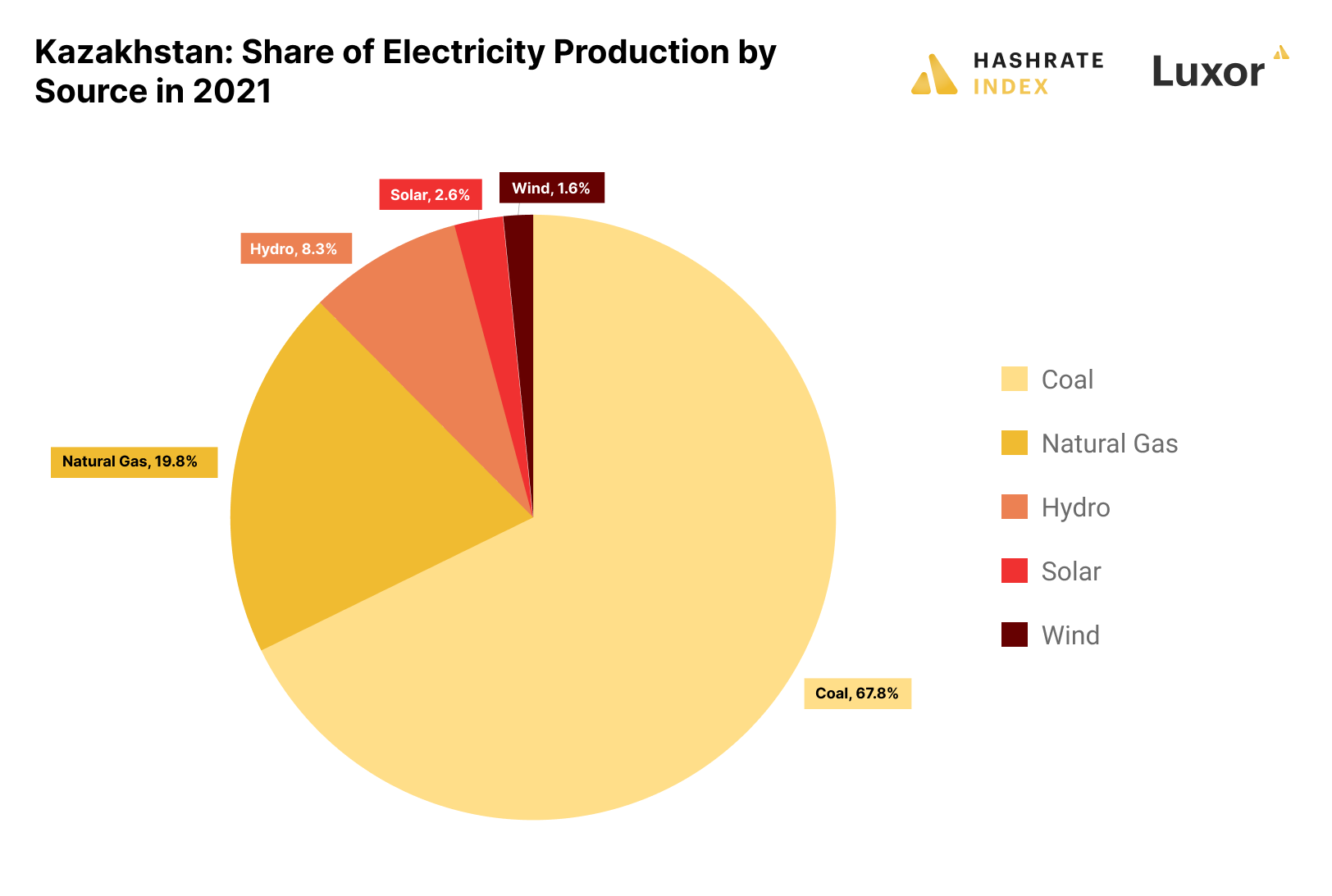

With its vast oil, gas, coal, and uranium resources, Kazakhstan is an energy superpower. The country is landlocked, with thousands of kilometers to the closest seaport, making it challenging to transport these energy resources. Coal has the lowest value-density of these energy sources, so Kazakhstan uses it for internal electricity generation while exporting most of its oil, gas, and uranium output.

In 2021, the country generated 68% of its electricity from coal, 20% from natural gas, 8% from hydro, and 4% from wind and solar combined.

Kazakhstan constructed most of its coal power plants during the Soviet era, and they now suffer from decades of wear and tear. Although the country is building several new coal power plants to replace aging ones, the share of wind and solar will likely increase in the coming years as the Kazakh government plans a significant buildout of these resources. The vast wind-swept steppes have decent solar and excellent wind potential.

You might find it bizarre that the world’s biggest uranium producer has no nuclear power-generating capacity. However, the country has plans to build new nuclear power plants totaling a capacity of 2.4 GW by 2035 that will be fueled by locally sourced uranium. Still, 2035 is far into the future, particularly for the high-time preference bitcoin mining industry. Therefore, coal will continue being the base load generation in Kazakhstan for the foreseeable future, albeit with slightly growing shares of wind and solar.

KEGOC, a state-owned company, operates Kazakhstan’s national grid, while several regional electricity companies handle distribution and sales. Private enterprises own most generation assets. Miners in Kazakhstan are incentivized to source power from private coal and gas plants to save transmission and distribution fees.

Kazakhstan is a massive country with vast distances. Most electricity generation is localized in a handful of industrial cities in the northeast of the country. These electricity generation and transmission hubs have also attracted the most mining capacity. These are places like Karaganda, Pavlodar, Oskemen, and Eikibastuz.

There is also some mining in the west, close to the oil and gas fields in the Caspian Sea. In this area, miners usually generate their own electricity either from associated gas or gas pipelines. The Kazakh mining industry will likely migrate toward this region to take advantage of associated gas from oil production, as it could be the only long-term solution for escaping the stringent regulation. We will likely also see some miners use associated gas from coal production in Karagandy.

Kazakh miners face new stringent regulations

The out-of-control growth of the bitcoin mining industry ultimately forced the Kazakh government to take action. After more than a year of uncertainty, the new law “On Digital Assets in the Republic of Kazakhstan” was implemented on April 1st. The government could have banned the industry but instead sought to provide a stable environment through stringent regulation - its standard procedure with industries it deems critical.

The new law has four consequences for miners. First, miners need to obtain licenses to operate. Secondly, miners can only use licensed crypto exchanges and mining pools. Thirdly, miners will be last in line for electricity supplies. Fourth, a mining-specific electricity tax is introduced.

In the coming sections, I will explain how all these factors impact the mining industry.

Miners can now only use licensed service providers

In addition to controlling the miners themselves through a licensing requirement, the Kazakh government also aims to get a complete overview of the bitcoin flow from the mining pool to the miner to the exchange. The government has, therefore, decided that all mining pools operating in Kazakhstan must obtain a license and report the miners’ income to the Kazakh government for tax purposes.

In addition, miners will have to sell their bitcoin on locally licensed exchanges. This requirement will be gradually phased in, with a need to sell 25% of the bitcoin locally currently, 50% from 2024, and 75% from 2025. Miners now have seven licensed exchanges to choose between, including Binance, which is known to cooperate heavily with the Kazakh government.

All Kazakh mining pools and crypto exchanges must be registered in the Astana International Financial Centre (AIFC), a regional financial and technological hub opened in 2018. The Kazakh economy depends heavily on commodities, so the Kazakh government aims to diversify into tech and finance by attracting companies from these industries into AIFC.

Miners are now last in line for electricity supplies

As mentioned, the rapid growth of bitcoin mining without a corresponding increase in generating capacity led to problems for the grid. The Kazakh government wants to ensure this doesn’t happen again and has, therefore, heavily regulated how miners can purchase electricity.

Previously miners were able to purchase electricity like any other business. According to the new law, they can only purchase electricity through the national power auction system KOREM, which will have a separate trading platform only for miners. The national grid operator, KEGOC, will set a quota on the mining auction system depending on how much electricity it determines to be in excess at any given time. Miners will then compete for this “excess” electricity through an auction. The excess electricity will likely be insufficient to feed all the miners, meaning this way of purchasing electricity will likely not be a viable solution long-term.

Another way to purchase electricity is by importing it from Russia at prices between $0.07 and $0.09 per kWh. These prices are too high to build a sustainable bitcoin mining business around. And why would anyone mine in Kazakhstan with imported Russian electricity if they can just set up shop across the border, pay significantly less for electricity, and face less stringent regulations?

The third and potentially only long-term viable way of purchasing electricity is through a direct contract with an energy producer. This energy can come from coal, natural gas, hydro, wind, or solar, or it can be sourced from associated gas from gas or coal production. As I will explain, solar and wind have tax advantages, but associated gas can be obtained much cheaper.

The new electricity tax sets a price floor for electricity

The new regulation will not only constrain miners’ access to electricity but also impose heavy electricity taxes.

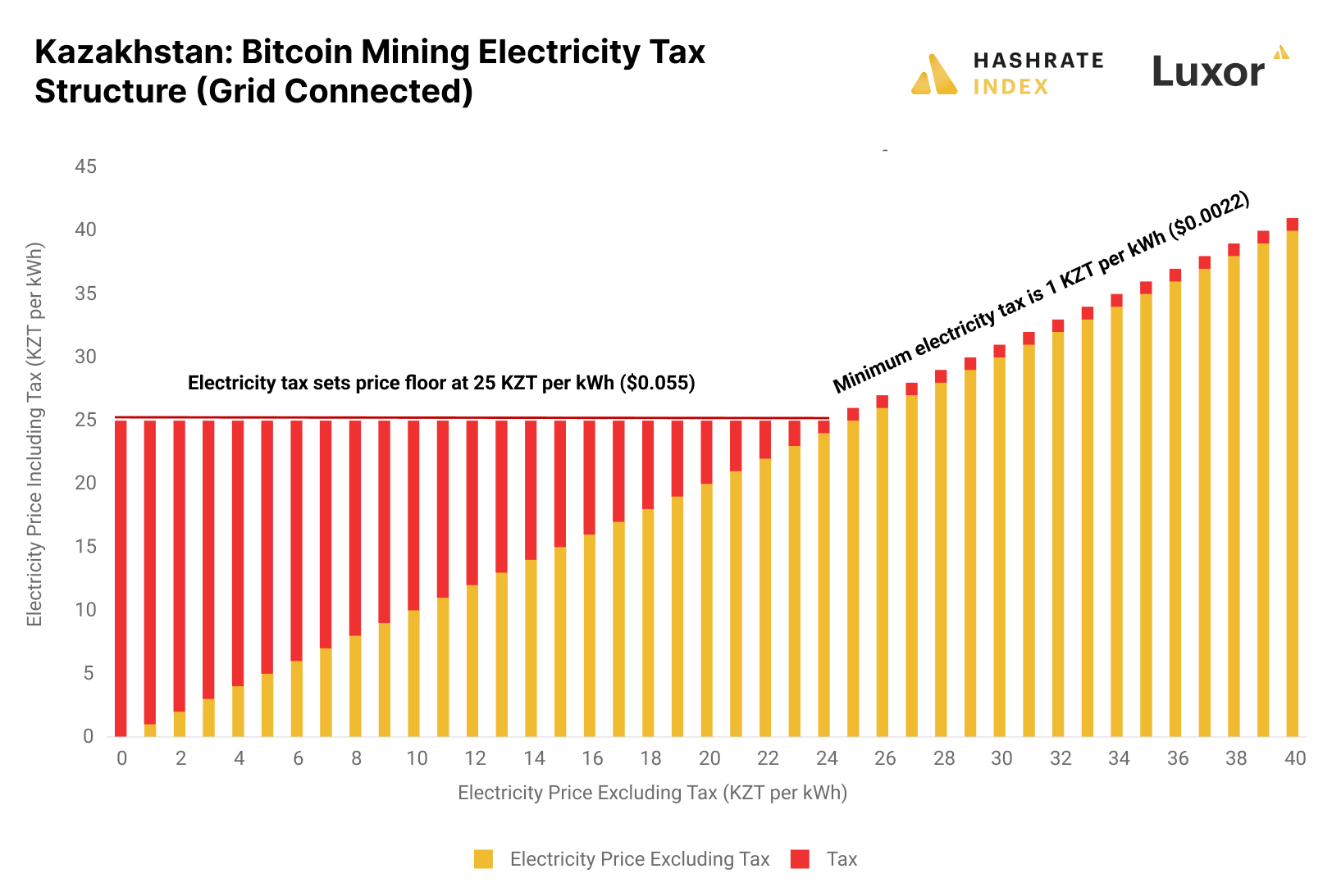

The tax level depends on how and to what price the miner sources electricity. We can split the taxes into three types. The most excessive taxation applies if the miner purchases electricity from the grid through the KOREM auction system or by importing from Russia and will effectively set an electricity price floor at 25 KZT ($0.055) per kWh.

I know it seems complicated, but let’s look at an example. Let’s say there is a period with massive excess electricity in the KOREM auction system, and a miner buys electricity for only 5 KZT ($0.011) per kWh. Then the electricity tax will be 20 KZT ($0.045) per kWh, driving the total price to 25 KZT ( $0.055) per kWh, like shown in the illustration below.

This taxation structure further reduces the viability of grid-connected mining in Kazakhstan. Even if miners could secure cheap grid-delivered electricity, the heavy taxation would ensure they paid a relatively hefty rate after all.

I don’t think it is a coincidence that the government structured the tax to create a price floor at $0.055 per kWh. This amount is close to the historical bear market break-even costs of mining using medium-efficiency machines, so it looks like the tax is created to extract as much as possible from the miners without completely killing them off. One thing is certain - the tax is not created to optimize the sector's efficiency, as it disincentivizes miners to secure cheap electricity.

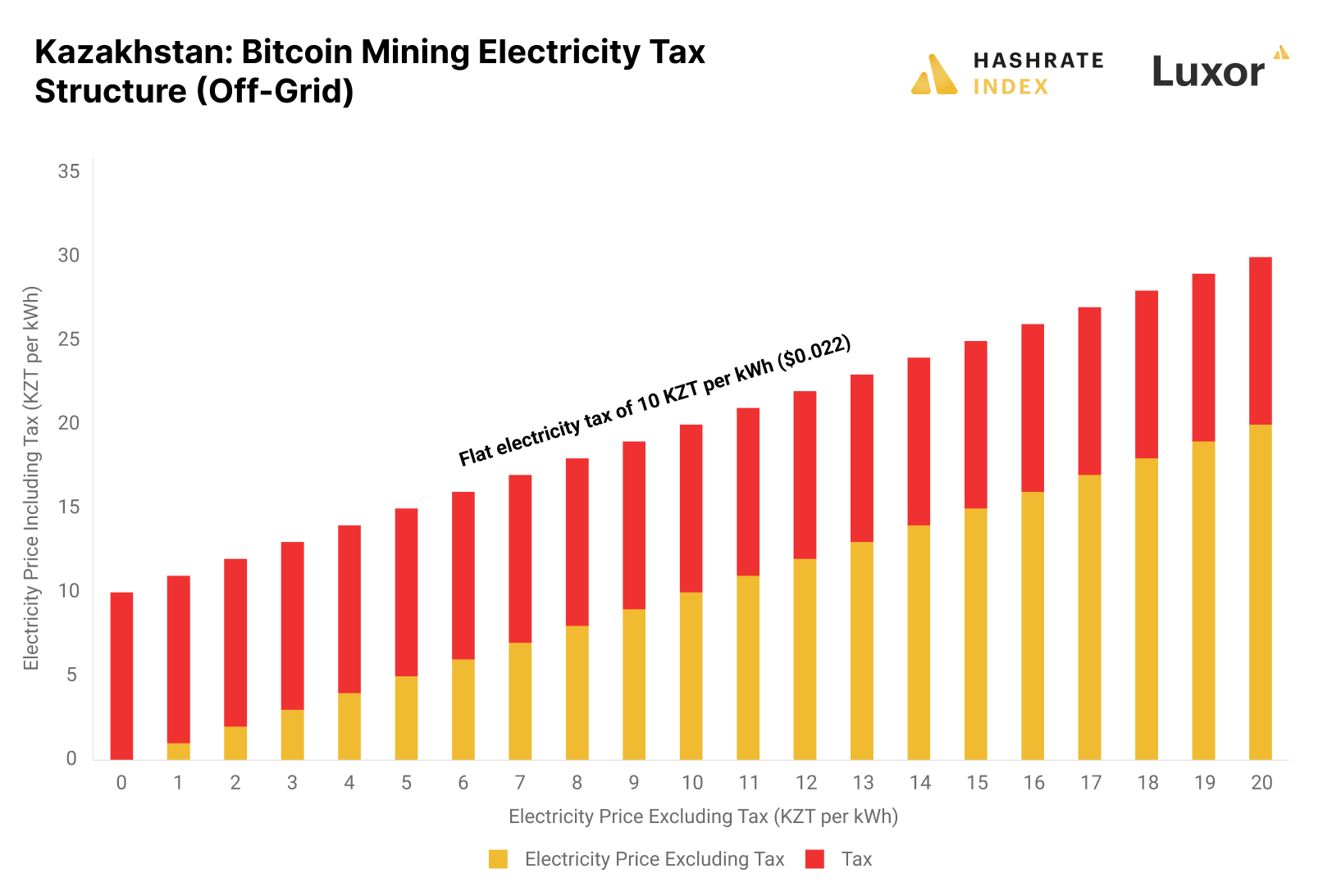

The second type of mining electricity tax applies to those buying electricity off-grid directly from non-renewable power producers. These miners will pay a flat electricity tax of 10 KZT ($0.022) per kWh. The government imposed this tax to prevent Kazakh power plants from mining instead of selling electricity to the grid.

A flat tax of $0.022 per kWh is substantial. Off-grid miners in Kazakhstan have traditionally been able to buy electricity at around $0.03 per kWh. After adding the new tax, these miners will now pay about $0.052 per kWh, which is not that competitive globally. In addition, if a significant amount of these power plants continue mining after the tax is implemented, the Kazakh government could further increase the tax in their efforts to milk the industry. Therefore, I’m not entirely sold on off-grid mining in Kazakhstan, but it is still a better alternative than grid-connected.

A more moderate electricity tax applies to miners purchasing electricity directly from wind or solar farms. These miners will pay only 1 KZT ($0.0022) per kWh. Such a tax is survivable, but the problem is that wind and solar energy is generally the most expensive in Kazakhstan. In addition, with only 4% of the total generation, there is currently not enough wind and solar to feed the high mining demand. Therefore, miners must build their own wind and solar farms to exploit this opportunity.

Operational conditions for miners in Kazakhstan

A critical but often downplayed consideration in bitcoin mining is climate conditions. Generally, a cool operating environment allows you to overclock more often using firmware like LuxOS, increase your up-time, reduce cooling infrastructure requirements, increase machine lifespan, reduce maintenance requirements, and ultimately increase your bitcoin production and operating efficiency.

Kazakhstan has warm summers and freezing winters. In the north, where most of the country’s mining industry is located, daily mean temperatures range from -15°C (6°F) to 21°C (70°F) between the coldest and warmest months. Most miners use hydro curtains for cooling during the summer. During the winter, the freezing weather could create challenges for miners, but miners solve this by reducing air circulation. Overall, Kazakhstan provides decent climatic mining conditions, at least compared to US mining hubs like Texas.

Another operational advantage of mining in Kazakhstan is the excellent access to labor. Kazakhstan has a young, hard-working population with good IT knowledge. Thus, it is generally easy to find qualified workers. Labor costs are also very cheap, around $0.002 to $0.0025 per kWh.

The future of bitcoin mining in Kazakhstan is uncertain

With the new law being implemented, the Kazakh bitcoin mining industry is at a crossroads. Either the law will provide the stable regulatory environment needed for the industry to grow sustainably, or its stringent taxation and power purchase rules will euthanize what is left of the industry. How the regulation will impact the sector remains to be seen, and I will update this article as things become clearer.

What is certain is that Kazakhstan has a power shortage problem that must be solved before the country’s bitcoin mining industry can return to its former gigawatt glory. The only way I see the bitcoin mining industry in Kazakhstan substantially growing in the coming years is if miners develop their own generation capacity. This can be from various sources, but the biggest potential is in associated gas, wind, and solar.

Another challenge Kazakhstan’s bitcoin mining industry must overcome is the shutdown of the foreign capital tap. After what has happened over the past year, it will be hard to find a foreigner who wants to invest in mining in Kazakhstan. This problem is exacerbated by better mining opportunities across the border in Russia.

Due to these challenges, there will be limited growth of the Kazakh bitcoin mining industry for the foreseeable future. Still, the long-term potential of mining in Kazakhstan is massive, and I'm certain the country will always be a substantial hashrate producer.

So, what can we learn from the sudden rise and fall of the Kazakh bitcoin mining industry? Two things. Firstly, political risk is always looming in bitcoin mining. In late 2020 and early 2021, most believed bitcoin mining in Kazakhstan was safe and that the Kazakh government was friendly toward the industry. Many foreigners hosted their machines there only to discover it wasn’t safe after all. I consider the political risk for miners substantial in all countries, particularly developing ones. Paraguay and Argentina might feel safe now, but who knows what could happen.

The most critical takeaway is that miners should avoid using subsidized or price- capped electricity, particularly in fragile electricity systems. The exploitation of subsidized electricity for mining bitcoin has attracted the wrath of numerous governments, including neighboring Kyrgyzstan. Electricity systems with subsidies or price caps also tend to be fragile due to underinvestment. My suggestion to miners operating in such countries is always to operate off-grid.

Thanks to Alen Makhmetov (Hashlabs), Didar Bekbauov (Xive), Denis Rusinovich (I&D Media und Project Advisory), Darkhan Munaitbassov (AQ Group), and Daniyar Mubarakov (Data Center Industry and Blockchain Association of Kazakhstan) for insights.

Are you scaling a Bitcoin mining operation and in need of mining software, services, or hardware? We can help. Feel free to DM me on Twitter.

Hashrate Index Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.