Flared Gas Bitcoin Mining 101: When it Does (and Doesn't) Make Sense

Flared gas and Bitcoin mining sound like a match made in heaven — but not all stranded gas is the same.

Bitcoiner environmental-capitalists have championed flared gas mining as a shining example of “Bitcoin fixes this” — and for good reason. However, a flared gas Bitcoin mine isn’t a simple plug-and-play operation; it’s highly complex and as nuanced and idiosyncratic as the oilfield itself.

Let’s dive a little deeper into this topic and examine when mining Bitcoin on flared gas is viable and when it is not.

Today, we conservatively estimate that there are over 150MW of mining operations deployed worldwide for various levels of flared gas mitigation. A few small operations pioneered the approach as early as 2016, and now the idea has had several years as a proof of concept at various scales and in various states.

This time last year, the White House released a report titled: “Climate and Energy Implications of Crypto-Assets in the United States” that caused a stir in the mining community. It isn’t particularly detailed, but the report does provide a surprisingly clear-eyed evaluation of the potential of mining off flare gas:

While the EPA and the Department of the Interior have proposed new rules to reduce methane for oil and natural gas operations, crypto-asset mining operations that capture vented methane to produce electricity can yield positive results for the climate, by converting the potent methane to CO2 during combustion. Mining operations that replace existing methane flares would not likely affect CO2 emissions, since this methane would otherwise be flared and converted to CO2. Mining operations, though, could potentially be more reliable and more efficient at converting methane to CO2.

We believe they’ve properly identified flaring as a grey area for proponents of carbon offsets through mining. The whole proposition truly comes down to the nature of flaring and venting rather than any value proposition from Bitcoin mining. One of the primary reasons a mine may or may not work with flared gas has to do with why the gas is being flared in the first place. Well operators typically do not flare gas if there’s any option to deliver it to market.

💡 Not all flaring is the same. Let’s go beyond a simple gas flare -> Bitcoin mine calculation and look at the technical and economic challenges of various types of gas.

6 Reasons Why Operators May Flare Gas From an Oil Well

- Temporary flaring at the start of production — Often called “flowback,” this temporary measure may be used to handle gas removed from frac water. Gas production at this stage is often low with inconsistent volumes and the well will begin to “gas up” as the hydrostatic pressure of the frac water in the well is removed. These are poor candidates for mines since the flare will only be on site 1-45 days typically.

- Emergency flaring during drilling or completions — It may be necessary to deal with gas influx from the reservoir before the production facilities are ready for use. With massive amounts of heavy equipment on location and high danger of fire, these situations are unlikely to ever see mining.

- Gas quality may cause an operator to flare gas — Natural gas is a conglomeration of various molecules; most are hydrocarbons but some of are classed as “waste gasses”. Common waste gasses include Nitrogen (N2), Carbon Dioxide (CO2), Hydrogen Sulfide (H2S), and (to a lesser extent) Helium (He). Nitrogen and Helium are rather inert but lower the value of the gas and will cause midstream pipeline companies to sometimes reject natural gas from a well, leaving it stranded. CO2 and H2S are far more corrosive and erode pipeline steel. H2S exposure can be fatal even at relatively low levels and can occur naturally in a reservoir or be induced by human error if drilling and completion water isn’t treated properly with a biocide to prevent surface bacteria from entering the reservoir. Bitcoin mining ultimately has a future here, but it will take significant technological revisions to consistently produce energy without causing environmental damage.

- Gas can become temporarily stranded if downstream facilities are shut in or have an emergency. These shutdowns could stem from regular plant maintenance or a plugged line. Many modern wells have small flares that rarely run as a contingency plan for these instances. Small volumes may be flared until wells can be shut in or pipeline pathways can be rerouted so that there are no pipeline explosions from over-pressuring. Inconsistency makes these flares poor targets.

- Geographically stranded gas is an excellent target for mining — Crusoe pioneered this approach in North Dakota with oilfields that couldn’t connect to markets because they lacked economic viability or couldn’t surpass regulatory hurdles. These long-term flaring situations are genuinely wasteful and both the operator and miner significantly benefit from the synergy even before the environment comes into consideration. The catch is that these wells are almost entirely oil wells and changes in oil commodity markets can cause operators to cease production even if the mine is still profitable. More than one miner has found that out the hard way.

- Economically stranded gas — This is gas that has historically been produced into a pipeline and is forced into flaring for economic or regulatory reasons not tied to the presence of pipelines. With increased regulatory burdens on pipelines, many midstream operators are electing to shut in old lines, even filling them with cement in some circumstances. This kills the market for all the wells connected to the pipeline and forces operators to find alternative outlets for gas, often resulting in the temporary flares coming into constant use. Alternatively, midstream companies may try to pass on regulatory and repair costs, resulting in untenable fees for gas where the well operator may pay for takeaway capacity. Flaring ends up being the economic path of least resistance for these wells.

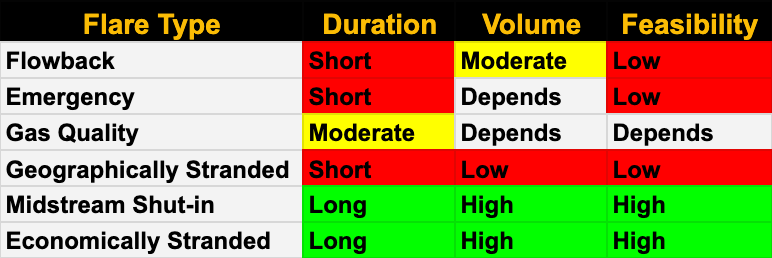

Now that we've addressed the reasons why oil drillers might flare on-site, let’s examine the feasibility of each type. The following is a table summary with our evaluations of gas production duration, gas volume, and feasibility of each type of flare gas.

Venting comes with other nuances, as gas escaping from produced oil may evaporate from tanks and other surface equipment. This may go through a Vapor Recover Unit (VRU)or may be left unmeasured and un-flared. Many tanks do not have pressure measurements so it can be hard to calculate how much gas is even available from vented sources.

The final component to stress is the proximity of wells. Depending on the field and whether wells are horizontal or vertical, it may be difficult to collect enough volume for a generator. Connecting stranded volumes may have regulatory and economic hurdles even with the well-intentioned plans of reducing energy waste. High prices for pipe and labor make collecting 5-10 wells into a single point source for a mine largely impractical and miners have been forced to evaluate individual well sites on the whole.

💡 Bitcoin mining has and will reduce flaring and venting and help bring the oilfield into a more ecologically-focused future, but it is not a one size fits all solution.

Flare gas mining will take a measured, practical review on a case-by-case basis to know if a mine is viable. Right now, there are plenty of opportunities as acceptance of off-grid/remote mining grows. The jury may still be out on the ultimate impact of mining with flare gas though. Maybe it will have staying power and significant impact, and maybe we will find that our continental-level statistics were a bit irrationally exuberant.

This article was co-authored by Kyle Drew, a Reservoir Engineer for Calyx Energy III & a cofounder of Nakamotor Partners.

Hashrate Index Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.