An Introduction to Hedging

Commodity markets are made up primarily of speculators and hedgers, although there are a lot of sub-types to those categories. The primary focus of a speculator is to take on risk in a market with the goal of making a profit. Examples of speculators include Hedge Funds, Private Equity firms, Proprietary Trading groups, and Market Makers. The goal of a hedger, however, is to reduce their risk exposure and gain more revenue certainty. A hedger can be an individual or company whose main business centers around a particular commodity, either as producers or buyers.

What is Hedging?

Hedging is often considered a complicated topic but at its most basic level, hedging can be considered as insurance for the risk exposures you have in your business. When people hedge, they are protecting themselves against the possibility of an adverse outcome. In financial and commodity markets, hedging generally involves the use of instruments called derivatives that can be used strategically to offset these adverse outcomes.

The most common derivatives used to hedge are forwards, futures, and options. However, there are many others as well. Each instrument used for hedging comes with pros and cons and may be leveraged for different use cases.

A Brief History of Hedging

The modern history of hedging goes back to the 1800s in Chicago. In the mid-1800s, Chicago was the center of the commercial agriculture industry, where farmers were selling grain to dealers who in turn, would then ship their grain across the country.

Farmers would produce grain during the spring and summer and then come to Chicago to sell it. Dealers would then offer their prices to buy defined amounts of grain. However, the amount of grain produced by farmers did not always equate to the demand and whatever quantity the farmers didn’t sell would ultimately go to waste. This dynamic forced many farmers and dealers into financial distress and often capitulation. Producing grain in advance, without any possibility of price certainty, did not provide any level of certainty for the farmers revenue.

However, around 1850, farmers and dealers came up with a better idea. Farmers would ask dealers if they were willing to commit to buy grain at an agreed-upon price, to be delivered at a future date. If the farmer and the dealer agreed, the two parties made a trade commitment that would then be added to the market chalkboard, holding both parties accountable for the transaction: the farmer to deliver the grain at the specified time, and for the dealer to buy the grain at the specified price.

And the modern forward contract was formed.

Example of Commodity Hedging – The Corn Hedge

So how does a forward contract work in practice?

For a simple example, assume a farmer has harvested 10,000 bushels of corn and is storing it for distribution.

- The farmer wants to gain revenue certainty and sells 10,000 bushels of corn forwards (or NDFs) at $6.75/bushel, the farmer is now in a hedged position.

- In this example, the producer is long (owns) 10,000 bushels of corn and is short (sold) the equivalent of 10,000 bushels of forward (of NDF) contracts for corn.

The farmer effectively hedges their harvest by selling corn forward contracts and locks in the price for their production, avoiding any exposure to adverse price movement in the market for corn.

If the price of the corn goes down, the hedge profits. If the price of corn goes up, the hedge incurs a loss. However, in this hedged position, any losses on the NDF contracts are offset by the increasing value of the physical grain inventory, and vice versa.

Other examples of commodity hedgers:

- Farmers and dealers hedge wheat, cocoa, sugar, orange juice, coffee, cotton, and many other commodities.

- An oil producer may hedge the price of a barrel of oil to cover operational costs from extracting oil from the ground.

- An airline might hedge their fuel costs to get revenue certainty from a fixed price for the next 6 to 12 months.

Hedging for Bitcoin Miners

As we have learned in recent history, the need for hedging applies to the bitcoin mining community as well. Bitcoin miners have 3 main risk exposures:

- Operational risk (power costs)

- Balance sheet risk (bitcoin price movement)

- Revenue risk (hashprice movement)

For their operational risk, miners can leverage energy derivatives (Forwards, PPAs, Futures, & Options). For their balance sheet risk, they have similar instruments in bitcoin derivatives. For their revenue risk however, they need to account for bitcoin price, network hashrate, block rewards, and transaction fees.

However, to manage this last risk, miners need derivatives based on hashprice, which embodies all four components in hashrate revenue.

Luxor’s Hashprice NDF

Hashprice is a term, coined by Luxor, that quantifies how much a digital miner can expect to earn in revenue from a specific quantity of hashrate.

In a non-deliverable, cash-settled forward contract, also called an NDF, the difference between the fixed price in the contract and the settlement value of the commodity at the expiration of the contract is paid in cash from one party to the other.

When trading forward contracts, two parties, often referred to as counterparties, must agree to certain key terms of the deal.

For Luxor’s Hashprice NDF, there are three main components that need to be defined:

- The first is the price of the trade, in this case Hashprice. Which for this contract is defined in $/PH/s/day. The minimum price fluctuation is 1 cent.

- The second component is the size of the trade, also defined in PH.

- The last component is the duration of the trade. Typically, these contracts are in 30-day increments but can be customized to any time frame

Hedging Hashrate

How can a Bitcoin Miner use Luxor Hashprice NDFs to hedge their hashrate revenue risk?

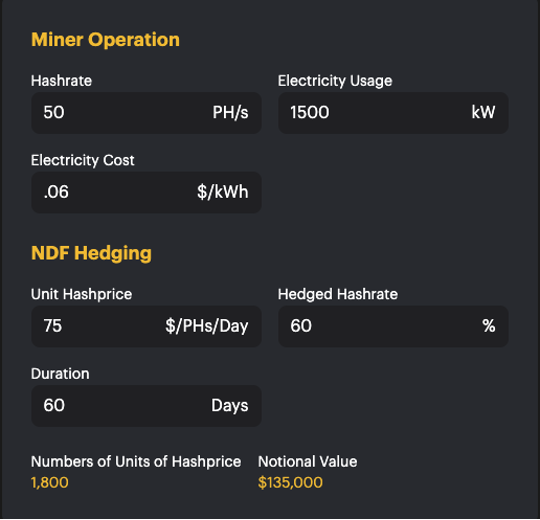

Let’s examine the case of a bitcoin miner who wants to "lock in" the price of their future production for 60 days. For the sake of simplicity, let's assume that the miner has 50 petahash (PH) and is looking to hedge 60% of their hashrate. As a hedge, the miner is looking to lock in hashprice for 30PH.

To do this, they could sell 1,800 (30PH x 60 days) Hashprice NDF contracts. If the miner sells these contracts at $75.00, they have locked in their revenue (hashprice) for that amount of hashrate.

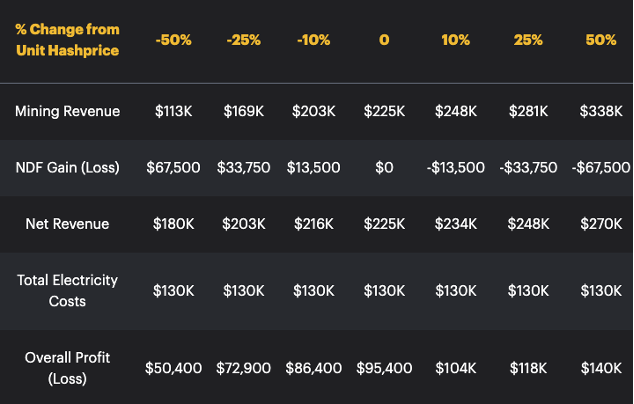

Now let’s assume that we fast forward to the end of the contract duration and run through some scenarios.

Scenario 1: Hashprice settles 10% higher

• The miner receives $248,000 in revenue from their normal operations

• The NDF hedge results in a loss of -$13,500

• The miners net revenue = $234,000

Scenario 2: Hashprice settles 25% lower

• The miner receives $169,000 in revenue from their normal operations

• The NDF hedge results in a $33,750 profit

• Net revenue = $203,000

• Net revenue w/o hedge = $169,250

Scenario 3: Miner hedges all their hashrate (rather than 60%)

• Net revenue remains a constant $225,000 for any % move in Hashprice, positive or negative.

In all 3 scenarios the hedge that the miner put on helped them achieve revenue certainty for a given amount of hashrate. This certainty helps the miner with risk management, capital allocation, covering operating expenses and much more.

Contact Us

Want to learn more or see the trading desk? Please visit Luxor's derivatives page.

Hashrate Index Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.